Definition: Armchair Acoustician

A play on the term “armchair quarterback”. One who suggests or implies they have particular insight or expertise in the study of acoustics when, in actuality, their experience is thin and their understanding of the subject is incomplete or in error. See also: Dunning-Kruger Effect

In this internet age we have all seen the questions people pose online that go something like, “Will a pure silver [insert instrument component] make me sound better?” These questions always get a reliable and highly predictable smattering of responses. There will always be testimonials from people who tried the exact change being asked about describing their results. Then there will always be people who respond citing “acoustic studies” (usually the same handful of studies are cited every time) that refute any belief that such a change will make any difference whatsoever and that it is all the placebo effect and it’s science and it was a double blind study which means it is better science, so good day, sir! I said, “Good day!”

I always cringe when I see such posts online. I recoil because the acoustic study responses have begun to become a meme. But not a good, funny meme. They are more and more beginning to resemble a minor league harmless conspiracy meme that latches on to the misapplication of data to turn real science into pseudo-science in order to meet the conclusion.

I used to roll up my sleeves and leap into the fray to defend my patch of reason about why their interpretation of the science was not entirely correct or how the study they were citing asked the wrong questions, but it can be exhausting. So I am writing this article so I can copy a link just as easily as the armchair acousticians can. Hopefully it will be of some benefit.

I will not directly cite any studies or scientific experiments in this article. I am not trying to disprove them (much). I will not be providing notes of sources. It is my view that the misinterpretations and flaws in frequently cited studies are plain to see and I hope that my pointing them out is enough. I admit that I am not a scientist and perhaps I may fit my own description of an armchair acoustician. I do, however, have a slightly annoying innate skill at seeing loose threads, questions not asked, and leaps in judgement that need more support, and have the compulsion to pick at them. THe armchair acousticians tend to paint over inconvenient questions with a broad brush. I have also been surrounded by first rate musicians literally for my entire life and that life experience calls into question in the most strenuous way the populist misinterpretation and misunderstanding of the science.

There are only a few acoustics studies that keep making the rounds in such discussions. They may be familiar to you. I aim to point out the common misunderstandings in the findings, the potential flaws in methodologies, and the disconnects within the scientific method on some studies.

I do not think the genuine science is wrong; I think the understanding and interpretation many musicians have of that science and how it applies to what they are seeking to answer is wrong. Some of this science is a pretty heavy lift, so I don’t blame people for relying on others who they assume know the subject better. But wrong is wrong. Hopefully I can correctly point out some of those wrongs.

What is a placebo?

The most common retort the armchair acousticians make in the face of anecdotal claims that defy their understanding of science is that is must be a placebo effect. The placebo effect is a psychological/psychosomatic effect. Essentially, the power of the mind creates a result the person expects. Most commonly it is used in medical trials to test the efficacy of a treatment.

As hypothetical illustration, in a test of 100 people where 50 in group A are given a drug and 50 in group B are given a placebo, 35 people in group A may show beneficial results to the drug, but 25 people in group B may show beneficial results. (There is also a control group C that receives no treatment to weigh against placebo responses) People in group B were given no medicine, but they don’t know that. The power of suggestion, faith, or whatever else has created an effect similar to that of the bona fide medicine.

The term “placebo” effect” has been used and overused in the discussions of acoustic perception for a long time, but people have begun to use it in a negative dismissive context. Looking back to the example I just made up, the people in test group B did show improvement, and isn’t that the point? You certainly can’t prescribe a nonsense medication, but you also can’t tell those 25 people in group B that they didn’t really get better, that it was all in their head. Who cares? They got better.

The placebo effect is a statistical tool more than anything. When it is used as a bludgeon to dismiss or discount another’s experience, it becomes the worst form of gaslighting.

There is no denying the power of suggestion is strong. Sometimes it can make people think or experience things that are not supported by science, but I maintain that the science is insufficient to just slap a blanket label of “placebo effect” on what someone claims to experience. Even if it is a genuine placebo effect, who cares? If a musician feels that some quality of their instrument is working to their benefit, then it will give them greater confidence, greater self-assurance, and likely lead to better performances. Isn’t that the point—to convey a musical message the best we can? How is thinking your gold plated mouthpiece allows you to perform better any different than not changing your socks the week of a performance “for luck”?

The Trap

The trap many people fall into is assuming that variable X will provide result Y. For example, a flute head made of a certain material will make the sound [darker/brighter/harsher/woodier/etc.]. If asking advice about how something may affect the sound or response of an instrument, tread carefully lest you draw the attention of the armchair acousticians waiting to pounce and regurgitate a misunderstood study.

Even if you get loads of responses that describe some sort of change and refute the objections, it is a losing proposition, because those helpful responses will be all over the spectrum. J’accuse! Placebo! It’s in all of y’all’s heads because you cannot come up with consensus! That’s not only science, that’s logic!

Everybody has a different physiology. Everyone’s oral cavity is shaped differently. Big mouth, small mouth, thin lips, thick lips. Some people have had orthodontic work done, and some have not. Everyone’s musculature is different. Most importantly, and most difficultly to assess, everybody’s preference for what they like is different. So, no. There will never be a consensus on what result changing variable X provides.

Story Time

Some years ago I took some saxophone neck screws to a studio at a music conservatory. My aim was to sell them for the ergonomic benefits against repetitive motion injuries, but I happened to mention in passing that some respected professional players had remarked on a change in timbre and response with these heavier screws, so the saxophone professor turned my visit into a little impromptu experiment.

To make a long story short, each of the 3 players who performed in the studio class noticed a difference when they installed the new screw and the listening audience heard it as well. What was interesting is 2 players who were playing on the same model instrument with similar mouthpiece set ups had opposite reactions and the listeners confirmed their descriptions. One installed the new screw and sounded darker. The other sounded brighter. The difference was one player was a stocky 5 foot 6 inches tall and the other was lanky and well over 6 feet tall. Even though they had similar playing pedigrees, they had wildly different body types.

If you want to have a serious discussion about tone quality and response in an open online venue, avoid the trap of suggesting X causes Y. Craft your question and responses carefully to avoid semantic arguments armored in pedantry.

The Vibrating Tube Problem

One of the acoustic experiments I said I would not cite, but I will describe in general terms, dealt with determining if the walls of a wind instrument could vibrate. If I remember right this experiment was performed in different applications at different times and the various scientists had similar findings. The findings were that the only conditions in which a wind instrument could have the walls of the material vibrate was to have the wall material so thin that it would not be usable as an instrument.

The experiments were sound, the math was good, and this experiment even appeared in some acoustics textbooks. The armchair acousticians in the musical community ate this up with their leaps to conclusions in what it “meant”. Any mention of someone claiming an instrument of material A vibrated differently than material B was instantly smacked down and these experiments cited. The amateur assessment became a silver trumpet bell is no different than a silver plated bell, which is no different than a lacquered brass bell, etc.

«Clearly, the science showed that the walls of wind instrument do not vibrate. Right? Ergo, it doesn’t matter what the bell is made of, right? That’s what they said… didn’t they?»

Well, yes and no. What got lost in the translation over to world wide web warrior speak was the use and context of vocabulary. To physicists, terms like “vibration” and “resonance” mean very specific things. Often such terms are defined someplace in the paper so there is no misunderstanding. I do not know if the terms were specifically defined, but the one experiment I studied made the context clear. In these particular experiments, the use of the terms was relating to the walls vibrating and creating their own sound independent of the excitation device.

But that’s not what musicians want or are even talking about. When an instrument is designed and set up really well, the player can feel a vibration in their fingers or in their face as they play. It is a tactile sensation, not a sound generating property of the material. The “vibration” that players refer is different than the “vibration” that was the focus of the experiments.

Nonetheless, the amateurs who have read a little bit of an experiment abstract use their partial or misunderstood knowledge to gaslight people. “Oh no, your instrument isn’t vibrating. Science tells us that is impossible. It must be in your head.” Unfortunately, I fear they have fooled themselves in the process and believe their (flawed) interpretation of the science so steadfastly that nothing can sway them, even an explanation of terms with two understandings. It’s the hill they will die on and dammit, they’ll take you down too in the process!

This is what happens when acoustic questions about musicianship and perception from the point of a musician are answered by non-musicians or unskilled musicians who are light on musical experience. The question is asked in one context, it gets mistranslated into another context, and then misunderstood when applied back to the original context.

The misunderstanding of the vibrating wall studies is used as a catch all bulwark against a wide variety of claims and experiences. For example, the fit of my head/neck/tenon is different and my instrument feels different — impossible because the walls don’t vibrate therefore there is nothing to dampen. Will the LeFreque device, heavy neck screws, or something similar do anything? Nope, it’s all sales hype and snake oil because the walls don’t vibrate. The convenient utility of the misunderstanding of the vibrating walls experiments can be found in almost every online musical acoustics debate out there.

Musician vs. Musicianship

Bear with me here—I’ll get to where I’m going…

One can be considered a “professional” simply by being paid for a job. It is the most basic distinction between a professional and an amateur. “Professionalism” is not a quality unique to professionals. Anybody can exhibit professionalism. It is more than a simple definition. It is a state of mind, the way one interacts with others, and the manner in which one moves towards an objective. Certain behaviors in interpersonal communication, organization, and prioritizing are tailored and crafted in the demonstration of professionalism. Some people have a knack for it and can develop it more easily than others.

Being a musician can have a similar relationship to the term musicianship. Being a musician can have a fairly low bar — string a few pitches together into a melody and you’re a musician in the most basic sense. Demonstrating musicianship, however, is a further refinement and application of many skills necessary to be a musician. Musicianship can certainly be developed and learned, and often grows through practiced listening and constant evaluation. Musicianship can cover a vast array of diverse concepts, but for the sake of this discussion, when I say musicianship I will be referring to the physical sensitivity of the player—the hearing, the feeling, and the otherwise sensing of stimuli that a player experiences.

So what? Why does this matter?

Just as one’s professionalism cannot be determined solely by how much of a professional they are—a minimum wage janitor may demonstrate more professionalism than the CEO of the company—the degree of one’s musicianship (physical sensitivity) cannot be assumed based on their technical proficiency as a musician. We would largely expect that a musician in the top tier of performing would also have a commensurate degree of physical sensitivity, but that is not always the case. We can certainly not assume that a player of lesser skill or experience has, by default, a lower degree of sensitivity. To complicate things, the way an individual interprets physical sensations is unique.

When a wind instrument is played the player gets all sorts of biofeedback. They can feel it in their lips, in their oral cavity, in their sinuses, in their abdomen, or maybe with things are just right they feel it in a particular place at the base of their skull. Skilled players may feel which muscles or muscle groups are activated in their face and mouth and by how much to produce the sound they want. They also may feel things through their fingers, hands, arms, and shoulders. All of this matches up with auditory feedback and the players with high degrees of this physical sensitivity musicianship will strongly relate what they hear with what they physically feel, consciously or unconsciously applying it to categorize what they find desirable or not.

I will get back to this topic later, but (spoiler) human sensory sensitivity has not been studied or quantified and certainly has not been correlated with acoustic data.

The Blind Spot of Listening Studies

One of the mainstays of the armchair acousticians is the listening survey. The most commonly cited of these wind instrument studies were done with flutes, trombones, or trumpets. The premise (I will not call it a hypothesis) is that a listener will not be able to tell the difference between materials used, for example, between a gold flute and a silver flute. The conclusion is often if the listener cannot distinguish the difference than there is no reason to “waste money” on gold this or platinum that.

I will not beat around the bush here. These studies are largely meaningless. To musicians they are the scientific equivalent of an internet quiz to see what type of cat you are. They achieve nothing beyond scratching an itch and largely prove nothing.

What the listener hears is largely the character of the individual player. If I go hear James Galway play, he’s going to sound like James Galway whether playing on silver plated nickel or solid gold. If I go to hear Wynton Marsalis play, he is going to sound like Wynton Marsalis whether playing on a Monette or Schilke trumpet. And if I go hear Sabine Meyer play, she’s going to sound like Sabine Meyer if she plays on a grenadilla, mopane, or plastic clarinet.

Obviously a skilled musician can make most well suited instruments sound the way they want and need them to sound. But do they have preferences? You betcha.

We hear the musician sounding like themselves on whatever instrument, but they may be working incredibly hard to do that. That’s their job. Jim Thorpe famously won an olympic gold medal running wearing mismatched borrowed shoes…but I digress.

When a musician finds a particular instrument that allows them to produce the output they desire with minimal effort, that is often what becomes a first pick instrument to perform on. They will know this instrument and its quirks and proclivities intimately. Tragically, this is a detail that is never accounted for in listening studies. In fact, using an instrument the player is familiar with is often expressly forbidden.

The Tyranny of the Double Blind

The fatal flaw in these studies is the insistence on it being a double blind study to avoid bias. In such a double blind study, the player does not know what they are playing on and the listeners do not know what is being played. Due to the nature of the double blind, the player’s preferred personal instrument is excluded since there may be tactile cues that tip them off.

The reason this model fails in establishing any results of meaning to musicians is the instrument a player prefers is a crucial variable that could be argued is corrupting the study by its absence or the lack of study of that instrument/player pairing.

When skilled musicians of high physical sensitivity have the good fortune to be paired with an instrument that is a good match for them, they tailor their playing practices around that instrument to produce the results they want. It is not simply the playing of an instrument. It is how that particular instrument is played. When playing on an unfamiliar instrument, a skilled player will still strive to sound the way they want, but they may have to work a little differently. Their embouchure may be imperceptibly tighter or looser, the air stream may be a little faster or slower, the angle of their tongue and openness of their throat may need more specific control, but the results coming out of the instrument are going to be remarkably similar.

A skilled player will pick up a foreign instrument and their manner of playing will adapt, often in seconds, and sometimes within the span of the first note played. It is understandable and not surprising in the least that a listening audience cannot distinguish a notable difference or pick up on identifiable qualities.

Oh ho! Well, Mr. Woodwindfixer guy, what about THE PLAYER telling the difference? Huh? Many of these studies asked the players if they could tell the difference or pick their favorite, and they couldn’t! What do you say to that?

I say, “big whoop”. As I said before, since the player’s personal instrument is not in the mix, they hare having to employ different voicing and playing mechanics, either consciously or unconsciously, to make the unknown instrument sound like them. Almost assuredly, every instrument in the blind batch will not be as good of a fit with the player as their personal instrument. I will rephrase… A blind test instrument may be an as good or better fit for a player once they can spend time to learn it, but these tests do not provide that.

Blind tests are short. They are not playing each sample for a prolonged period of time to learn the ins and outs and character of the instruments. The players often have mere minutes. Proper evaluation of an instrument to determine a good understanding of its qualities takes days or weeks. Blind tests are like speed dating and you expect them to know what gift they will give on their 10th wedding anniversary.

They can’t pick out the gold flute blindfolded. Big whoop. Unless the tester says, “I don’t know what that is but I’m buying it now!”, it really doesn’t matter what the instrument is made of. After all, what matters is what makes the player most comfortable in expressing themselves musically.

Listening tests want to be like the Pepsi Challenge where participants sample different cola drinks and reveal which they prefer. They are not asked to choose which one is Pepsi. In order for any such condition to be reliably sampled for statistical meaning, the familiarity of the participant with the flavor of different drinks must be documented and applied. Likewise, if a player has never spent a lot of time playing any trombone but their own, what value is there to ask them to identify different bell materials?

The Big Hole

What is missing from so many of these blind tests that claim validity simply because they are blind is the acknowledgement and utilization of the musicianship I mentioned earlier. The degree of human perception and sensitivity musicians possess has never really been studied. Thanks to misunderstood experiments and irrelevant listening/playing studies, people do not see the need to do so. They think it is a settled matter, but that accedes to the flaws I have described.

How can someone claim “the science” says one thing when “the science” is incomplete? Multitudes of musicians have preferences over instruments or components of instruments made of different materials. Yet, the misinterpretation of science and misapplication of scientific methods has allowed people to gloss over the human side of things — the science says it can’t be, so it must be in their heads.

This is not mass hysteria on the part of musicians. When musicians of diverse skill levels and backgrounds are all expressing that they think there is a difference, “the science” should take that as a suggestion that there is more to determine, more to explore, more variables to check.

To paraphrase Neil DeGrasse Tyson, the thing that takes care of bad science is better science.

The Need for Modern Experiments

Many of the foundational experiments, in addition to being misinterpreted, are just plain old. Some were performed in the 1950’s or 60’s or earlier. That doesn’t mean they are bad experiments, but they are technologically limited. We have better microphones. We have better speakers. We have unbelievably more computing power and digital sensitivity. Despite the vast technological advancements, there have been scant efforts to even recreate some of these experiments, instead extrapolating the old data to fit a different set of questions. This works on assumptions from the start.

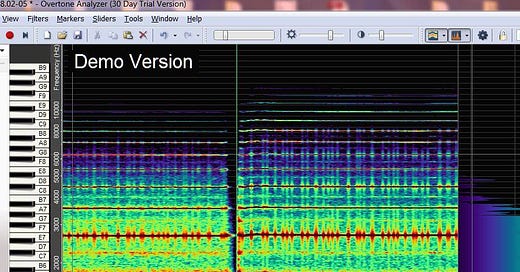

Below is a photo one of my European repair colleagues shared on Facebook almost a decade ago. He was trying out one of the LeFreque attachments on his flute and played into some basic off-the-shelf recording software to see what it would tell him. (The LeFreque is a device the maker describes as a “sound bridge” between joints of an instrument. The maker’s claims of how and why it works are dubious in the face of science, and that has led many to shun the device. Many others swear by it.)

In the photo, the horizontal lines represent overtones or harmonics above the played pitch, A. The overtone series above the A can be seen clearly at the next A above, then the E, followed by the A and so forth. Whatever software this is displays the weakening strength of the harmonic within the sustained A. The left side of the picture is him playing without the LeFreque. The right side is with the LeFreque.

At minimum, this should make people see that something is going on here. If the interpretation f the vibrating wall experiment is to be true, then the material doesn’t vibrate and no change outside of the vibrating air column will make a change to the sound. If that were true, these side by side images would be identical. WHy are they not?

Spurious claims by the maker and individual testimonials or rejections aside, it should at least strike some curiosity and suggest the need for a focused study into if this is a consistent phenomena, or if it is something subjective or random. This was done by a musician just playing around with free software in his home music studio. Imagine what an acoustics lab could determine.

Do you Hear it or Feel it?

There are no experiments that I know of that focus on the strength of harmonics or combinations of harmonics present above the fundamental musical pitch. In my college acoustics class, the professor said a clarinet sounds like a clarinet because it is missing every other harmonic, which is a fact many people know. He also said an oboe sounds like an oboe because of an unusually strong upper harmonic (I forget which one specifically). This may also be why some soprano saxophone players can sound like oboes (I prefer to sound like a flute).

It is my hypothesis that not only do the strengths and arrangements of harmonics influence what we hear, but they also influence what we prefer as players. But before we can get into the rabbit hole of quantifying what people prefer, we need to determine the extent to which people can perceive and sense differences. Can a simple change to the instrument make a perceivable change? I think yes, but it has never been tested beyond misappropriating results from other experiments and leaping to unfounded conclusions.

Who wants to make some better science?

Jeff Dening is the owner of Jeff’s Woodwind Shop in Baltimore, MD. He is always looking for ways to make musicians’ jobs easier and the understanding of their instruments more accessible. Visit www.woodwindfixer.com to get in contact with Jeff.

I think another thing worth remembering is what we are using these tools to achieve. People tend to think it's simple like sports - what sneakers generate a 1% faster time- but our goals are not so simple. It's more like artists paintbrushes, there's probably not a good empirical way of looking at what brush is better, but I'm sure painters find the brushes that let them express themselves the best without impediment. We stand on shoulders of 300 years of engineering, refinement and countless trial and error. When new materials present themselves, try it by all means, but the players will decide over the decades what tools let them express freely.