I spent the first 4 parts of this series writing about the development of woodwind pads and an overview of many different types people may encounter. That is all fine and dandy if you are into stockpiling trivia with which to impress your friends and confound your enemies. But what does it mean to an instrumentalist or an educator or a technician?

In this part I will revisit some salient points of the different types of pads and perhaps offer some more specific details. I will provide the pros and cons of each type of pad from my professional experience. Indeed, I may provide information here that could help one determine which pad may be most suitable to their needs.

This article will be released initially for paid subscribers only but will be made available to the public in time.

What is the best pad?

Anyone who knows me, and probably anyone who has read my various articles, will have an inkling that I do not answer broad brush questions directly. What does “best” mean? Best for the player? Best for the technician? Best for durability? Best for precision? Best for cost? Best for installation time? Best for feel under the fingers? Best for tone quality? It all depends, but in an unusual twist there is an easy broad brush answer to this broad brush question.

The best pad at any given moment is the pad the technician working on the instrument is most comfortable installing in that instrument in the circumstances at hand. While there are some unstudied acoustic properties to consider, the most important thing is that the technician knows what they are working with and knows how to handle the inevitable curve balls that come up within their understanding of the behavior of that pad in the context of their techniques.

That’s a bit of a mouthful, so think of it this way. I would rather go for a 15 mile hike in shoes that I know fit my feet well, than try the “best” hiking shoes out there because someone (even lots of people) said they are “the best”. If they don’t fit as well, if they rub on my pinky toe, if there is slightly different arch support, if their traction on the sole is different than I am used to, they are simply not the best for me.

Technicians choose the pads they use for a variety of reasons. Some are very particular and narrow in their focus of what they like (for me it is precision of material dimensions). Others have a broader perspective and their wheel house is to work within the wider tolerances that is expected for some material to achieve success. There are valid arguments to be made for or against either side of the scale.

A Bit More About Felt

In part 2 of this series I described the bladder pads most of which have a core made up of a felt disc. Since the overwhelming number of woodwind pads out there are of this type, I need to cover some more details, because not all felt performs the same function.

Types of Felt

In ye olde tymes, the felt that came to the woodwind pad making industry came from mills supplying the garment industry, mostly hats. Today, the bulk of the felt manufactured is made for industrial purposes. The needs and demands between these two applications of felted fiber are very different. At minimum, one can imagine that felted fibers made for clothing are going to have a different attention to texture than industrial felt, which may be intended for some sort of insulation or gasket.

If one were to do a google search for felt today, much of what comes up describes 2 types of felt: needle felt and pressed felt. This can be a murky topic to get into because there is similar nomenclature between the old ways of doing things and the modern ways of doing things, but the definitions or understanding of those processes is different. A technician with a lengthy pedigree may understand the terms in one way which are not the same as how the terms are defined today.

It should be said that there is no standardization of nomenclature within the pad making industry. The cross over to the felt industry offers little clarification. One major industrial felt maker says on their website, “A non-woven fabric, felt holds its edges and will not unravel when cut.” But if felt is a “non-woven fabric”, then why does every woodwind pad maker out there advertise “woven felt”? Perhaps it is just this one company’s process, but doing research on your own without direct industry knowledge can be confusing and create more questions than answers.

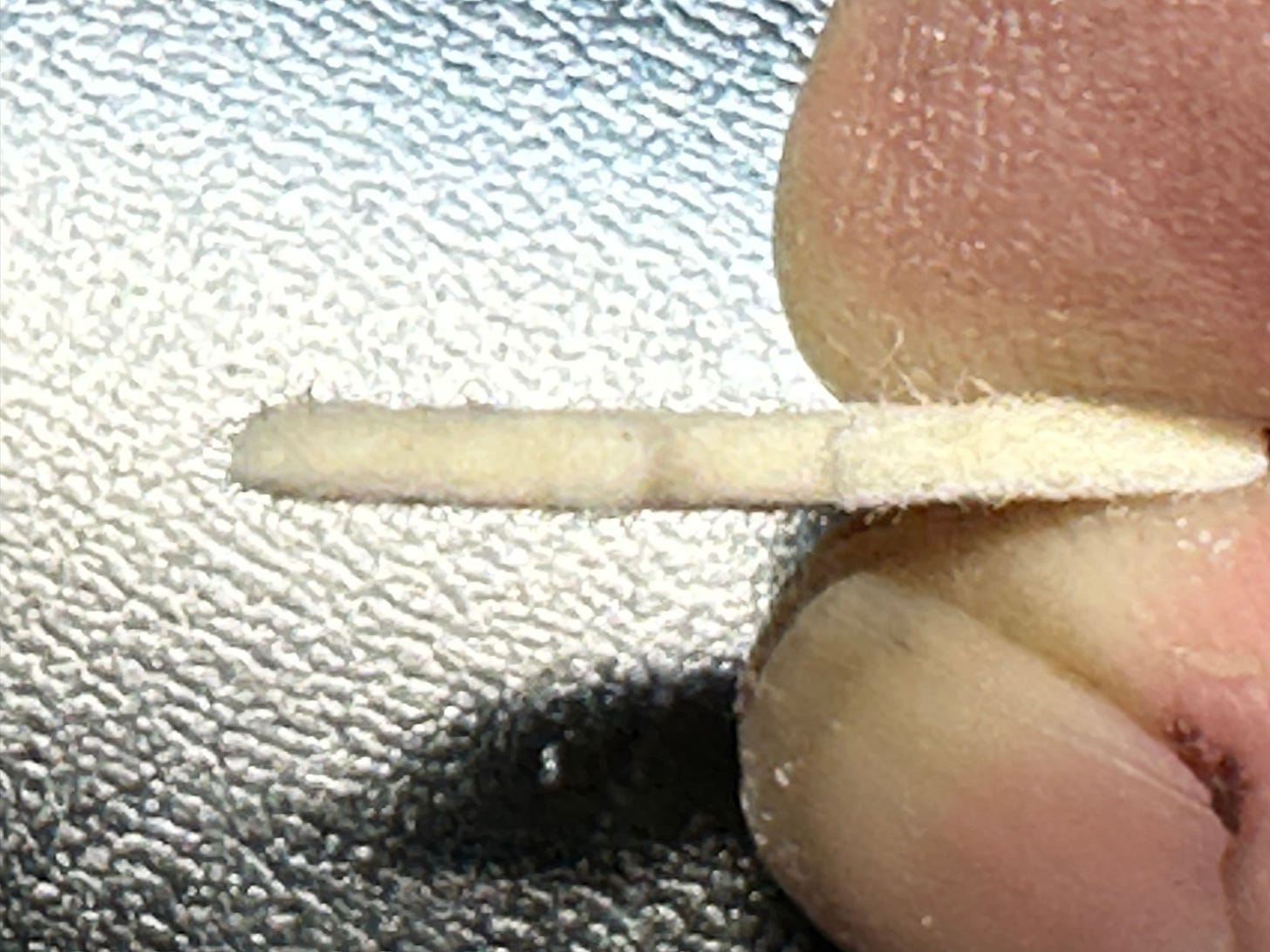

To my understanding, felt (for the purposes of woodwind pads) is a product of the natural scales on wool fibers being forced to bind together through some sort of manipulation or abuse. Moisture, heat, friction, and compression are the main ingredients to turn wool fiber into felt. One could have a process that arranges raw fibers in a uniform thickness to create the fabric, or one could have a pre-woven fabric of a known thread count and a known thread or yarn gauge and turn that into felt.

The physical qualities and structure of the felt matter to how a pad will behave and what installation process is most appropriate. In the broadest general sense, pads marked as “pressed felt” will be firmer than those marked as “woven felt”. But there are many qualities of felt in both those listed as “pressed” and those listed as “woven” with an unknown amount of overlap. To hopefully reduce confusion in this topic, I will refer to pads created from a woven fabric as (wait for it…) woven felt and pads made of an unwoven structure as pressed felt.

The primary difference in structure is in a woven fabric it is a matrix of over-under-over-under thread arrangements. There will naturally be places in the fabric where the fiber is double thickness and immediately next to it is a thin spot or a void. These thick and thin spots blend into the felted fabric to be largely unnoticeable. When felted the structure contributes to the felt’s loft and density, but they can also create hard and soft spots detectible under the highest scrutiny. This can be a feature or a flaw depending on what you need in a pad.

High quality pressed felt (in the old definition) is made similar to paper with wet wool fibers mixed into a slurry and compressed into molds to form large blocks. The blocks are then cut into sheets which can be sanded to final thickness. (There are other ways to make pressed felt sheet, but this is the most precise way.). The fiber arrangement is randomized but the density of the material is very consistent. This style pressed felt is often very firm. Pads requiring a larger diameter or thickness generally are not made of true pressed felt.

The term Needle Felt pops up from time to time. In the present felt industry definition, needle felt has fibers running vertically where pressed felt (of woven or unwoven origin) has fibers running horizontally. Needle felt is made by repeatedly punching needles through the array of fibers to get them to felt together. This sort of felt in its pure form is generally not used for pads. However, there is a process called “needling” that piano technicians use to make piano hammers and dampers more firm by poking the felt piece multiple times with a needle-looking implement. It is possible that pad makers advertising “needle felt” may have had their woven felt “needled” to make it more firm. Without inside production knowledge, I cannot say for certain what specific terms used by various pad makers actually mean. But this is my educated guess on this topic.

At the end of the day what matters is the pad behaves in an expected way. If trying something new, techs should always sacrifice a pad or two to tear the pads apart and see what is really going on inside. For players concerned about making sense of all of this information, trust your tech’s decision making process.

A Bit More About Pad Coverings

For the most part, bladder pads are wrapped in some sort of animal product; usually goldbeater’s skin or leather. Here are some details one may see and wonder about.

Goldbeater’s Skin Pads

The most common question that pops to people’s minds is color. They see white pads and they see yellow pads. Is one better than the other? In a word, no.

Back in the far off and long forgotten times of the 20th century, the yellow skins were advertised as “treated” and I remember in my younger days some yellow pads having some sort of water repellant added to them. That idea didn’t last long.

This material is a waste material from abattoirs and meat processing that has found another use. I have been told that the yellow color comes from the tanning process when cleaning and preserving the material and that the white/transparent material is actually now more expensive and getting more difficult to find in consistent good quality.

What matters as far as this material is concerned for pads is the number of layers. The material is very tough, but to offer a bit of extra protection, most of the pads out there wrapped in goldbeaters skin have 2 layers. Some pad makers offer triple skins. I do not see the triple skin necessarily as an improvement. Causing one layer of skin to fail requires some work, but then you have a split in a skin or a flap of pad skin fluttering around set to cause all sorts of fun anomalies. No technician that I have ever encountered sees a compromised skin and leaves it alone because there is a back up underneath it in place. They just replace the damaged pad. I am unsure what an additional layer of skin would gain, but perhaps some techs like the way they behave.

Leather

Larger pads do not function well with goldbeaters skin. For a period of time the Leblanc alto and bass clarinets came with large sized pads of this material and they were miserable to deal with. Instead, the preferred covering is leather, typically from goats. Sheep leather has also been used and kangaroo leather is also a fine material.

One may see the term “pneumatic leather” thrown around. This simply means the leather is air tight. Some people make a big deal about air tightness mattering—if a pad leaks through the skin it is no good, they say. But to the contrary, the acoustic scientist (CWRU and Cleveland State) and clarinet researcher Arthur Benade is known to have said that some instruments (clarinets and bassoons) play better (by whatever definition “better” entails) if they don’t seal up like a glass coke bottle. Much of this Goldilocks amount of “just-right” leakage would happen through the pad skin.

Unfortunately for the armchair acousticians who insist upon a condition of solidly air tight being the mark of a “good pad”, they cannot and have not established what difference it makes and how much air leakage through the pad skin matters. Personally, I seal up pads I use to make them air and water tight so I have a baseline from which to operate. One cannot provide a consistent and predictable result if the natural materials have a varying degree of built-in flaws.

The big difference between the leathers used in pads is the thickness and flexibility. How the flexibility of the leather interplays with the density of the cushion is crucial to how the tech chooses to install the pad, how it may feel under the fingers, and how it holds up over time.

Pros and Cons of Different Pads

JWS Preference rating explained: Every technician has their own preferences influenced by their experiences, their customer demands, and the nature of work they do. The ratings I am putting on pads are in the context of how well a certain pad may suit its purpose at Jeff’s Woodwind Shop with my sort of customer traffic. A pad I rate at 8 or 9 out of 10 may be well suited for what I need, but another shop that is less experienced with that pad or has an instrument that would be better suited with another pad may rate it at a 4 or 5/10. Likewise, a pad I rate at a 5 may be the go-to workhorse pad for another shop that garners a 7 to 8.5 score. Your mileage may vary.

Felt—Goldbeater’s skin

Woven Felt

JWS Preference rating: 4/10 to 7.5/10 (brand and circumstance dependent)

Uses: Piccolo, Oboe, Clarinet, Flute

Pros: Flexible material of known characteristics, inexpensive, durable, able to accommodate moderate imperfections in tonehole or mechanism.

Cons: Many installation techniques are mired in old techniques from when felt was treated with mercury. Susceptible to humidity and temperature changes. With very specific techniques can be installed very precisely, but that precision has a limit to it.

Pressed Felt (randomized fiber)

JWS Preference rating: 6/10 to 8/10 (brand and circumstance dependent)

Uses: Piccolo, Oboe, Clarinet, Flute

Pros: The most dimensionally consistent of the felts. A high precision pad material. More stable than other felts for environmental changes.

Cons: Can have more key noise. Installation can be more fussy and laborious. There are practical limits to the diameter and thickness that is functional for pads.

Felt—Leather

*Leather wrapped pads almost universally use woven felt

Traditional Leather (kid)

JWS Preference rating: Pisoni Pro pads 8/10, others 5/10 to 7.5/10

Uses: (common) Saxophone, Harmony clarinets, Bassoon, (less common) Soprano clarinet

Pros: Durability. Ease of installation and tolerance to tonehole or mechanism imperfections depend on the specific pad construction.

Cons: Leather pads are getting expensive in recent years. As with goldbeater skin pads, many installation techniques are antiquated and insufficient to work well with modern pads. Some tanning processes in recent years have produced pads for some makers that tend to get sticky.

Kangaroo Leather

JWS Preference rating: Music Medic Chocolate Roo (brown)- 8/10,

Sax Gourmet (black)- 8.5/10, Roo (white)- 9/10

Uses: Saxophone, Bassoon, Harmony clarinets, Soprano clarinet, (less common) Piccolo

Pros: Unsurpassed durability. The strength of the leather allows it to be used in much thinner pieces with greater consistency.

Cons: Most kangaroo leathers in use are unsealed, resulting in porous leather. This adds another step to installation to create a waterproof/airtight pad. Cost. The thin leather requires (or allows) a firmer felt to be used to maintain structure and a firmer pad require more refined installation techniques.

Cork pads

JWS Preference rating: (hand shaped and sized) 9/10

Uses: Oboe, Soprano clarinet, Some use in piccolo, aperture keys on larger instruments

Pros: Exceptional durability. Potential for customization for size, profile, and seal is incredibly high.

Cons: Very labor intensive to install well. Material will get harder with time and be noisy in similar time it takes other types of pads to fail in other ways.

Synthetic pads

Valentino Greenback

JWS Preference rating: 6/10

Uses: Piccolo, Oboe, Soprano clarinet

Pros: Inexpensive, easy to install, waterproof

Cons: Structural collapse on keys sprung closed. Gets sticky quickly in the presence of sugar/starch blown through instrument.

Valentino Masters

JWS Preference rating: 8/10

Uses: (common) Soprano clarinet, Bassoon wing joint, (less common) Piccolo, Aperture pads

Pros: More dimensional stability than Greenbacks. OEM pad for many brands or models of instruments. Waterproof. Available in white, tan, and black.

Cons: Gets sticky quickly in the presence of sugar/starch blown through instrument. Limited thicknesses available. One density available. Modification required if more room for glue is needed.

OmniPads

JWS Preference rating: 9/10

Uses: Piccolo, Oboe, Soprano clarinet, Bassoon wing joint, (less common) Aperture pads, Flute

Pros: Multiple thicknesses, multiple densities available. Waterproof. Shape allows room for glue with no modification.

Cons: Only available in white. Gets sticky in the presence of sugar/starch.

EZ Pads

JWS Preference rating: 8.5/10

Uses: Piccolo, Oboe, Soprano clarinet, Bassoon wing joint, Simple system flutes and piccolos

Pros: Economical. Multiple thicknesses (the thinnest pads available), multiple densities available. Waterproof.

Cons: Only available in white. Modification is required if more room for glue is needed. Gets sticky in the presence of sugar/starch.

Engineered Pads

Straubinger (original)

JWS Preference rating: Flute- 10/10, Piccolo- 9/10, Clarinet- 9/10

Pros: Extremely precise. Nearly inert to environmental changes. Eliminates need for mechanical compromise. Allows for the lightest touch and fastest response. Pads sizes available in increments smaller than 0.25mm

Cons: Must be installed correctly to function as intended. Not available without training. Will reveal mechanical/structural failings and require them to be considered or rectified. Incorrect installation almost guarantees premature pad failure. Should only be used on instruments of superb mechanical quality. Older flutes require a conversion process which is largely reversible. Cost.

Straubinger Phoenix

JWS Preference rating: 9-9.5/10

Pros: Will tolerate slight flaws in toneholes and mechanisms. Will withstand greater pressure before failure. Nearly inert to environmental changes. Can easily stand in for or replace thin felt pads without conversion. Available to purchase without training. Excellent option for flutes that aren’t quite stable enough for original Straubinger or JS pads.

Cons: Even though no training recommended, diligent and refined installation is required for success. Learning curve for techs without handmade flute specialist training. Durability can lure techs to use some felt pad techniques, which do not turn out well. Cost.

Muramatsu MA (Lotus)

JWS Preference rating: 10/10

Pros: Best engineered pad system out there. Incredibly precise and durable pads.

Cons: Only available for certain Muramatsu models. Cost.

JS Gold

JWS Preference Rating: 9.5/10

Pros: Very durable pad under normal use and regular care. Novel pad design has merit. Flute pads are applicable wherever Straubinger or MA pads may be considered.

Cons: Pad cushion can be damaged easily. Specialist training recommended. Saxophone pads limited to 0.5mm sizes. Proper saxophone installations require extraordinary work. Cost.

Pisoni S2

JWS Preference rating: 9/10

Pros: Available without specialist training. More tolerant of imperfections than Straubinger or JS pads.

Cons: Specialist training recommended. Not quite as precise as other engineered pads mentioned. Design differences compared to Straubinger do present limitations on precision.

Imperial

Avoid these pads.

These pads are a rough approximation of the Straubinger concept with a machined plastic cup under the skin. Some years ago they were installed in some “step down” import models of a respected major flute maker. I have found many to have the skins applied too tightly, distorting the plastic cup and creating rampant instability.

At the Woodwindfixer’s Bench is a publication of Jeff’s Woodwind Shop, a repair shop for professional musicians in Baltimore, MD. Visit www.woodwindfixer.com for more information, to contact Jeff, or to schedule a repair. Summer COA times are available now but will not last for long.